About Philip Hedley

THE EARLY YEARS

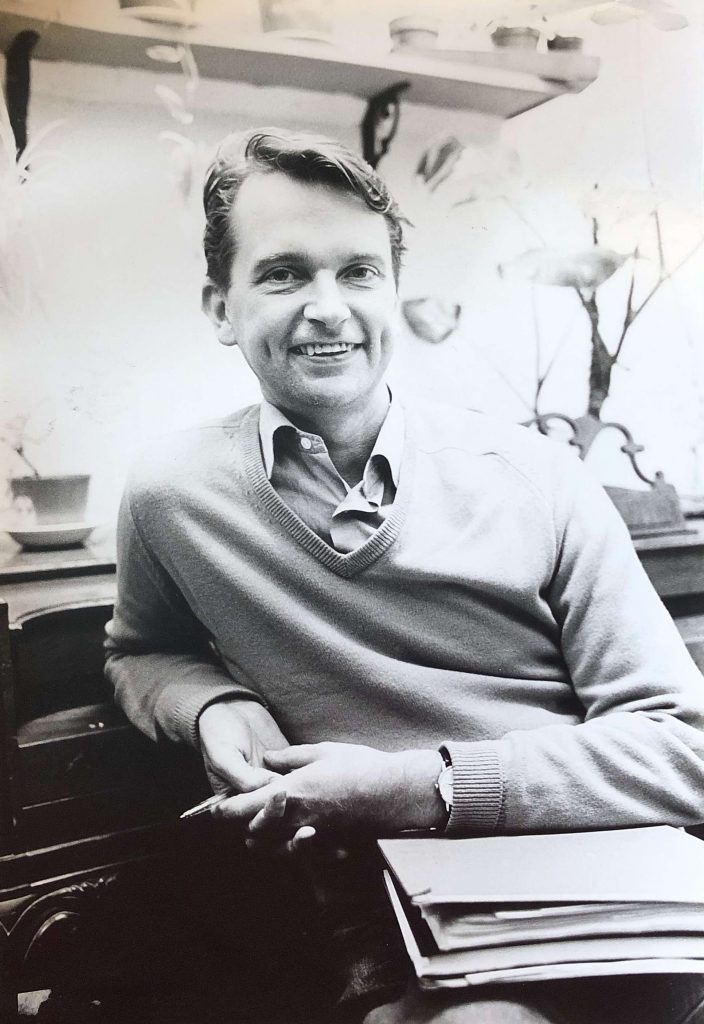

Born in Manchester England in 1938; his growing interest in drama was the consistent element throughout his schooling in Manchester, London, Melbourne and Sydney. He was spoilt with praise as an actor at the University of Sydney and when he returned to England in time for the swinging sixties, he thought it would be an actor’s-life-for-him. Seeing a production directed by the innovative director Joan Littlewood revolutionised his thinking about theatre.

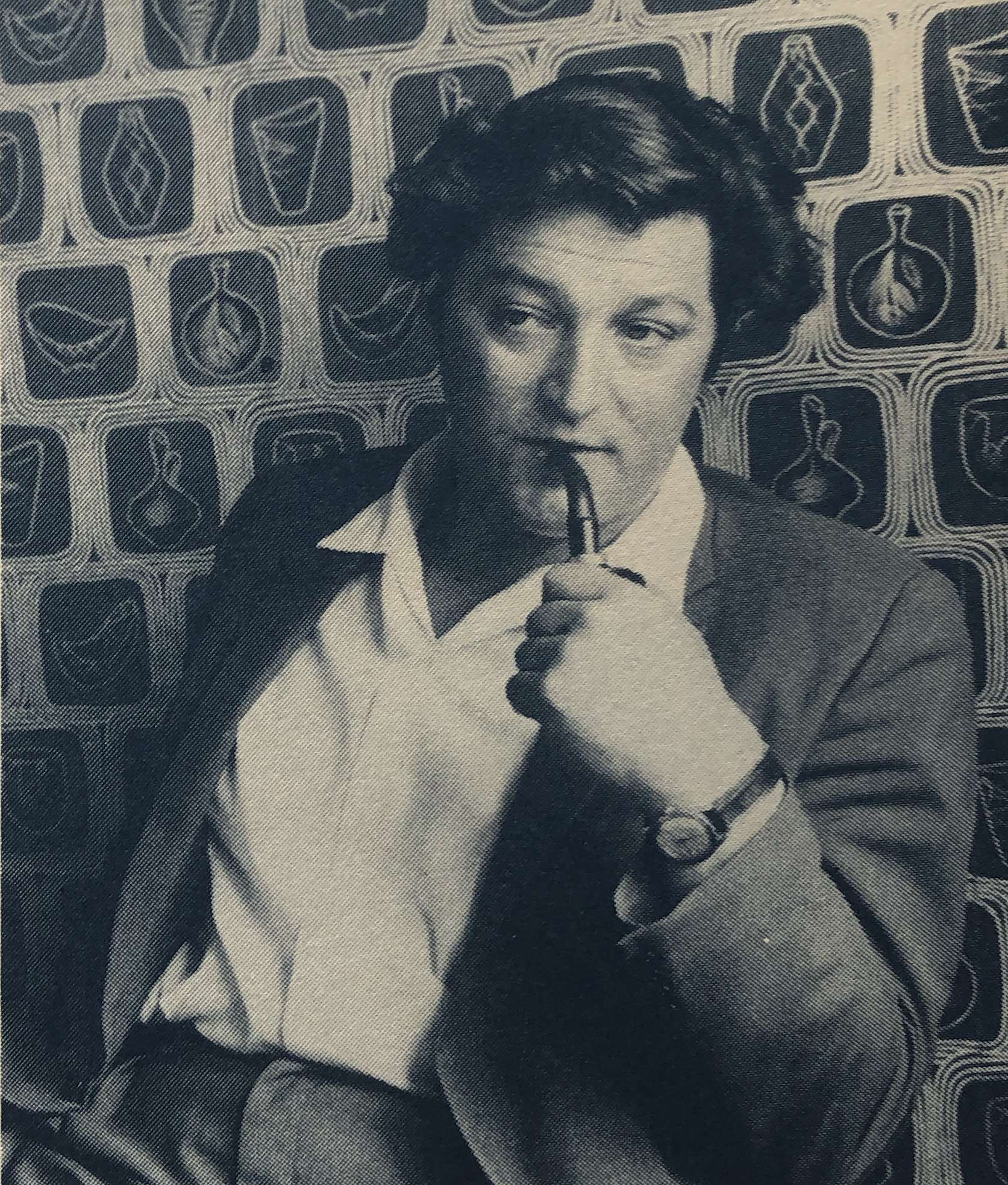

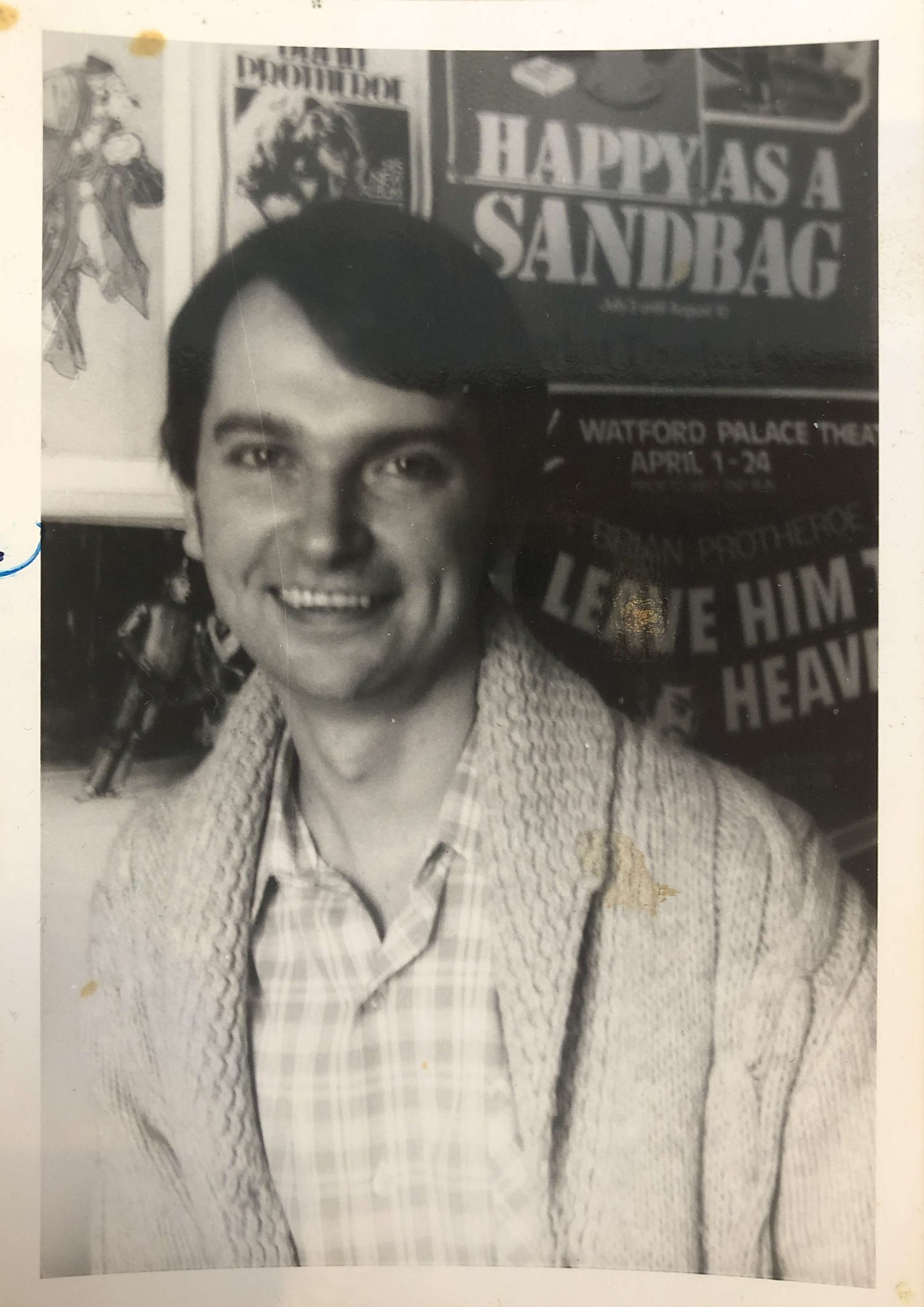

In 1961 two members of Littlewood’s company opened the East 15 Acting School based on her rehearsal methods, which in turn were based on the acting theories of Stanislavsky and the movement theories of Laban. Philip Hedley went out to the school in the East End of London as soon as he heard of it. The next day he was a founding student of the school. On graduation two years later, he became an actor/ASM for a year at a repertory theatre, the Liverpool Playhouse, but that experience convinced him he was a director, not an actor. So, he became a teacher at East 15 Acting School to give himself experience directing plays, for three years. He went on to direct plays for LAMDA, for the Royal Court’s young people’s programme and for the Watford Palace Theatre.

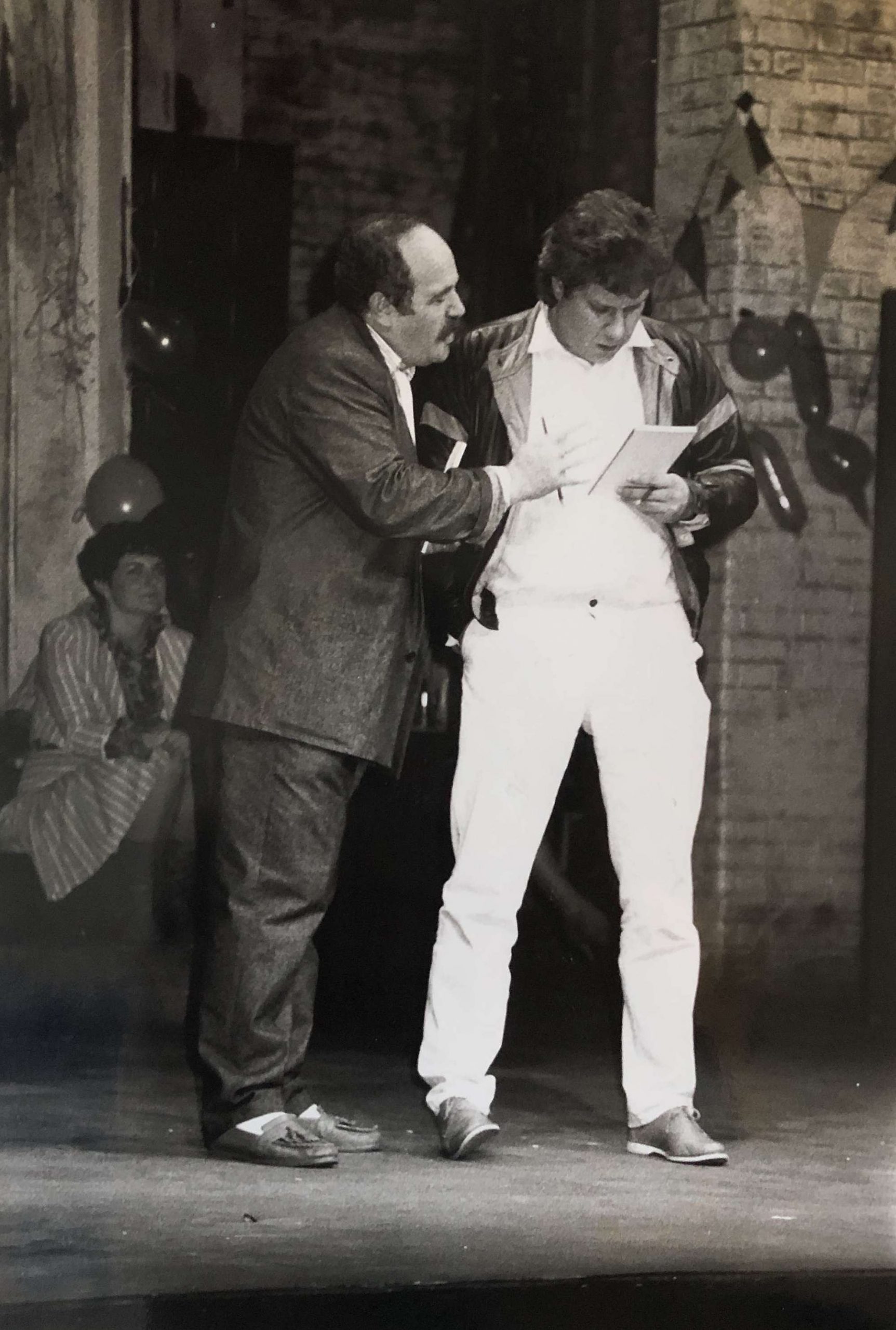

Lincoln Theatre Royal company In THE SERVANT OF TWO MASTERS by Carlo Goldoni, directed by Philip Hedley, 1968

His production of Sheridan’s ‘The Rivals’ at the Lincoln Theatre Royal was so successful they offered him in 1968 the post of Artistic Director, which he held for two and a half wonderfully productive years, during which he directed twenty-five plays and produced twenty more. He relished the joys of working with a permanent company of actors on a great range of plays in which the director could deliberately cast parts against type for the actors to extend their range.

The actors worked extraordinarily long hours, performing in the evenings and rehearsing the next play during the day. But they would also perform a music hall on Sunday nights in pubs and other venues around Lincoln. They’d do lunch-time shows occasionally too. They became such a united company they are still meeting up over fifty years later.

This was followed by working in repertory for two years at the Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham, which had an emphasis on young people’s work. Several of the actors were stalwarts of the Lincoln company. Hedley directed new plays by Henry Livings and David Cregan at Lincoln and he did two more of their plays at the Midland Arts Centre.

During 1973 and 1974 Philip was delighted to be asked by Gerry Raffles, the administrator and owner of the Theatre Royal Stratford East, to take on an unusual dual role of being both assistant to him and assistant in rehearsal to Joan Littlewood. It proved to be, as he hoped, two years of extraordinarily valuable experiences, typified by the accompanying photograph of him on the roof of the Theatre Royal dressed as Queen Elizabeth the Second, a role he was thrown into at two hours’ notice.

Philip Hedley as Queen Elizabeth II in COSTA PACKET by Frank Norman, directed by Joan Littlewood at Theatre Royal Stratford East, 1972

He directed only one production at the Theatre Royal at this time, which was to have been a revival of Joan Littlewood’s version of ‘A Christmas Carol’, but no-one could find the script of Act One and so that had to be improvised in rehearsal.

Meanwhile requests were piling up for Hedley to return to full-time directing, especially to stage the musicals by an author he had discovered in Lincoln, Ken Lee. This led him to accept guest productions in eight different regional English theatres, plus two productions a-piece in Vancouver and Sydney.

He became particularly known for his ability to free a company of actors up to get them working creatively together. Typical of the reviews he would get with this quality in mind are two he received for his production of ‘The National Health’ by Peter Nichols with Australia’s leading company of actors at The Old Tote in Sydney: “There is over all an assured and relaxed ensemble playing of the kind one was beginning to despair of in the Old Tote Theatre Company, and a feel of common purpose behind the work which gives the whole play a sense of conviction.” (Katherine Brisbane, The Australian). “The actors look like a team at last; the performances are so far ahead of what most of these actors have done this season that one feels like cheering.” (Greg Curran, The Sunday Australian).

L-R: Geraldine Wright, Yvonne Edgell, Lesley Duff and Darlene Johnson in HAPPY AS A SANDBAG by Ken Lee, directed by Philip Hedley at Ambassadors Theatre, 1975

Hedley had a particularly stimulating experience in the Sudan staging a play with twenty teachers who were withdrawn from classes for two months to learn about how to direct a play with their own students.

Meanwhile Ken Lee’s musical, ‘Happy as A Sandbag”, attracted West End interest and Hedley staged it at the Ambassadors Theatre. It had good reviews but no stars and it nearly closed after a three-month run. Hedley detected how few of the ticket agents in the West End had seen the show and he involved the cast in a sales campaign which meant the show stayed on for a year and was joined in the West End by another Hedley/Ken Lee production, ‘Leave Him to Heaven’, at the New London Theatre.

THE RESCUE OF THE ROYAL

Over a five-year period three artistic directors had failed to find a formula to make that theatre work after Joan’s departure, and by autumn 1979 the Arts Council was threatening to withdraw its subsidy if Hedley could not, within two years, justify its continuation.

He took up the challenge, and from a standing start, sought out shows to connect with local, East End audiences. There were pantomimes and Variety Nights, sometimes with star names. Events ranged from local school shows, to West Indian poets, to the North East London Police Choir. Joan Littlewood suggested a Victorian melodrama, which transferred to the West End. There was a new musical actually set in the Theatre Royal itself, with music by Ray Davies of The Kinks. There was Hamlet with a celebrated director, Lindsay Anderson, and there was a political farce about Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power, which received the excellent publicity of provoking ‘questions in the House’.

What really raised hopes the Royal would survive was the first play by Nell Dunn, called ‘Steaming’. Set in the East End, it packed the theatre and transferred immediately for a run of over three years in the West End. The Guardian commented “It seems the Theatre Royal Stratford East has finally found a management with both a taste for the popular and welcome audacity.”

Hedley followed this success by confirming his adventurous but local policy with four new plays, three of them set in the East End and all written by young, first-time authors.

It became certain the Theatre Royal would keep its Arts Council grant when, a few days before the decision deadline, the Arts Council’s Director of Drama was quoted in The Times as saying, “Philip has taken a very bold line, and he does seem to have found a dramatic vocabulary appropriate to the area.”

What the Arts Council did not mention was that the ‘bold line’ Hedley had taken included sacking those in charge of the finances and the bar, which involved at one point employing a bodyguard to protect him from threats of bodily harm. In Hedley’s twenty five years, from 1979 to 2004, as director of the Theatre Royal, such high drama off-stage occasionally rivalled the drama on-stage.

GOING LOCAL

The Variety Nights became a regular monthly event, concocted and hosted by a popular local actor, Kate Williams. The Evening Standard newspaper caught the spirit of these Sunday night events thus: “Geriatric gags and brand new sketches, bizarre contortionists and dressy drag queens, loud, brash and often extremely rude.” Famous actors from long-running TV series would pop in for the joy of playing in a comedy sketch to a very lively audience.

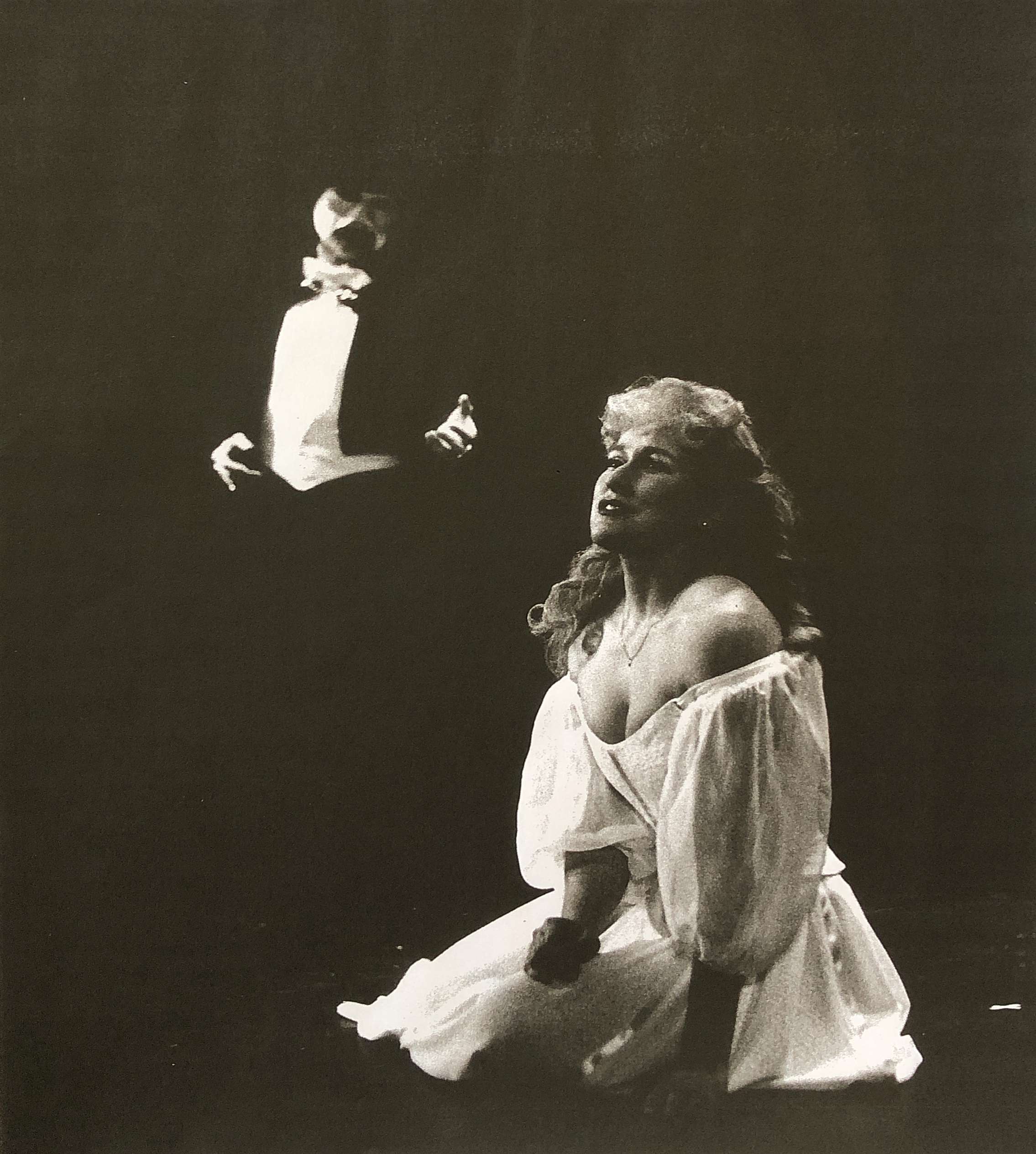

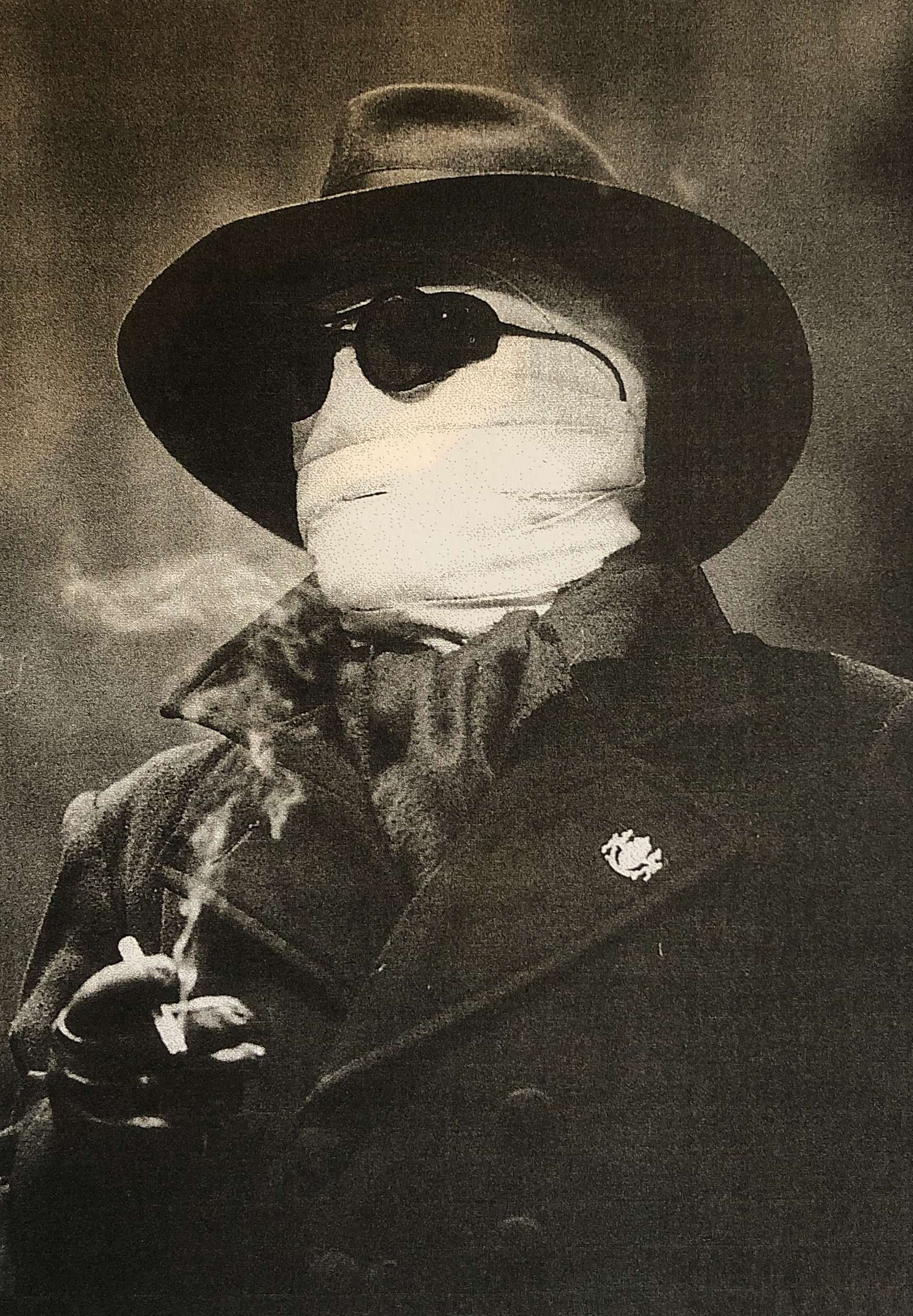

The originality of these Variety Nights, their impromptu style mixed with displays of top class expertise, somehow became the heart of the building. Playwrights the theatre wished to commission were encouraged to attend them and to take advantage if they wished of the easy, relaxed style of the give-and-take between the stage and the audience the Royal was acknowledged to have. This style was seen too in Ken Hill’s adaptations of popular novels like ‘The Invisible Man’ and ‘The Phantom of the Opera’, both of which transferred to the West End.

Another populist strand was the creation of shows around the private lives of famous entertainers, such as Old Mother Riley from Music Hall, Josephine Baker from French revue, Fatty Arbuckle from silent film and Sammy Davis Junior from American showbiz. The one show of this genre to transfer to the West End was imported from Australia with one artist, Robyn Archer, playing no less than ten famous women singers.

The audiences became, as in Joan’s later days, an attraction in themselves for coming to Stratford East. As Michael Billington wrote in The Guardian, “Stratford East audiences are generally marvellous. Indeed, if I was compiling a good audience guide they would go to the top of my list.”

Nearly all the plays at Stratford East in Hedley’s time were premieres and many of them dealt with social issues, sometimes comically, sometimes highly seriously, but always from a local point of view. The topics dealt with included the unfulfilling work given to young people on employment schemes, old people being treated in an infantile way in care homes, libraries closing, the damage being done to the National Health Service by the Tories and the narrowing of the curriculum in schools, particularly in relation to the arts. In a play objecting to a new unpopular tax, the poll tax, when some characters were preparing on-stage to go on a protest march, the audience cheered when they realised they could hear real-life people protesting on the same issue outside the nearby town hall.

PIONEERING BLACK AND ASIAN WORK

Our local black and Asian communities were of course fully represented on-stage as being involved in all the social problems, along with issues such as racism and police violence which particularly related to themselves. The Theatre Royal commissioned more black and Asian plays and employed more black and Asian actors than any other British theatre at that time. In recognition of the fact that black and Asian artists were rarely offered employment as a director, Stratford held three short courses for black and Asian would-be directors. Many graduates of these courses are working in theatre today.

In the 1990 Prudential Awards for the Arts, the Drama award was won by the Theatre Royal with the following judgement, “Under the present leadership of Philip Hedley, in a time of restriction and entrenchment in the arts the Theatre Royal Stratford East have increased their programme, developed an enthusiastic multi-racial audience of every class and age group, and most successfully promoted new writing with particular emphasis on populist, Afro-Asian, and young people’s work. This is an extraordinary achievement for a theatre of such substantial size but with restricted resources.”

Top row L-R: Robbie Gee, Brian Bovell and Sylvester Williams

Middle row L-R: Michael Buffong and Roger Griffiths

Bottom row L-R: Victor Romero Evans, Eddie Nestor and Gary McDonald

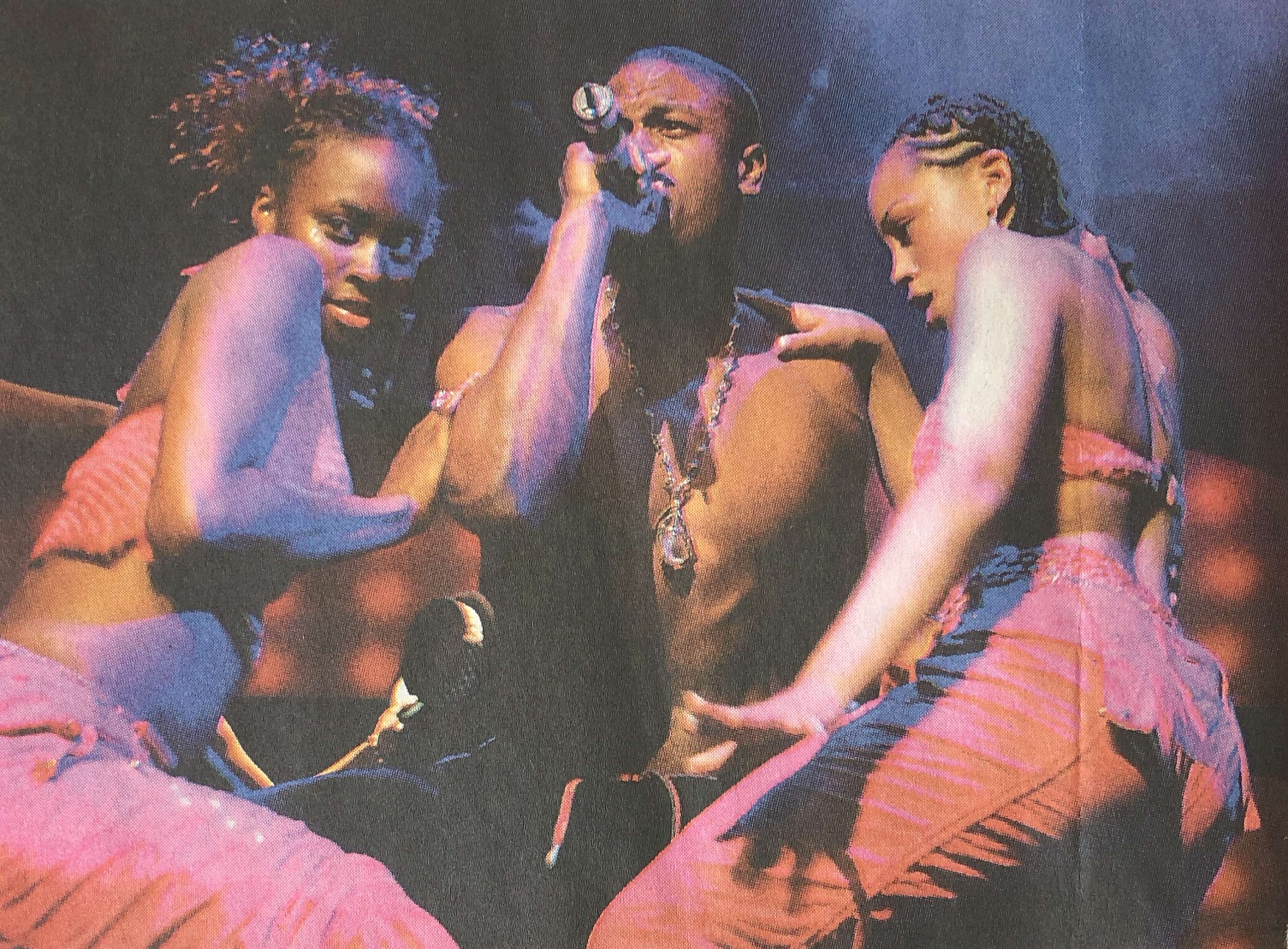

ARMED AND DANGEROUS written and performed by The Posse, 1992

In the nineties Stratford East gained a reputation for trusting black and Asian artists who approached it with ideas for a show. Examples abound. Eight young, black male actors, calling themselves The Posse, asked if they could stage a show at the Royal to illustrate what life was like for black men living in London. They wanted to write it, direct it, act in it and market it. Hedley agreed and the show was a great success at the Royal and on a national tour, and it was a learning experience for the staff of the Theatre Royal.

Top row L-R: Josephine Melville, Beverley Michaels, Joanne Campbell and Suzette Llewellyn

Bottom row L-R: Janet Kay, Suzanne Packer and Judith Jacob

ON THE LEVEL written and performed by The BiBi Crew, 1993

This was followed up by seven black actresses, calling themselves The BiBi Crew, taking the same journey. The Royal then encouraged a group of African actors and then a group of Asian actors to create their own shows. Finally, four black comedians, male and female, also created their own shows, sometimes solo, sometimes with other actors.

In yet another first in the nineties the Royal backed a new South Asian company, led by Keith Khan, to create the first British version of a Bollywood musical, with two Bollywood stars leading the cast. The show, ‘Moti Roti Puttli Chunni’ and its audience got rave reviews. The Guardian said: “Played in two languages the show offers a brilliant, pop-theatre marriage of East and West.” The Financial Times praised the theatre: “Nowhere else in the London theatre is there such a sense of direct participation”, and added “The audience on the first night was a huge ethnic mix; they all loved it. Part of the pleasure is simply being there.”

EPICS AND RISK

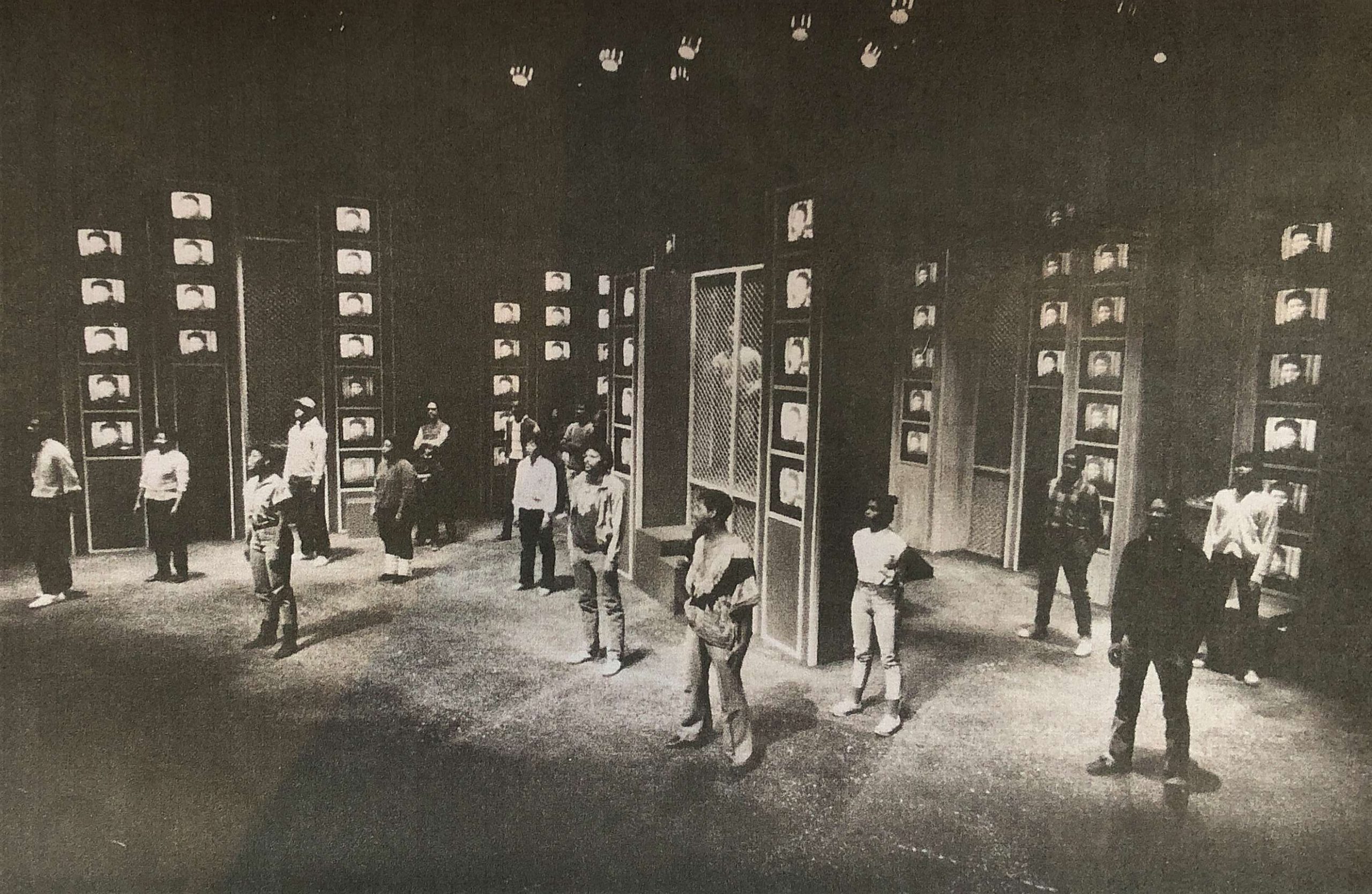

For example, he imported from Chicago a show called ‘Project! A musical documentary’. It had a very large cast, mainly of young black actors, enacting scenes of violence among tenants in tower blocks in a notorious estate, or ‘project’, which the performers actually lived in. Hedley saw it as an apt forewarning of times to come in the UK. The topicality of the show helped sell it and the risk paid off, despite the unhelpfulness of the American embassy when they realised the message behind the show.

Another example of large-scale risk-taking was the staging of the British premiere of ‘The Public’, also with a large cast and many expensive-to-create, surreal settings. It was by the late Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca, who never thought it would be staged, because of its homosexual themes. Hedley wanted to do it, partly because he had available the perfect director/designer for it, ULTZ, and partly because he’d discovered it at a time when there were huge public protests going on about a new law called Clause 28 which was opposed to anything being taught in schools which could be thought to be favourable to homosexuality as a life style.

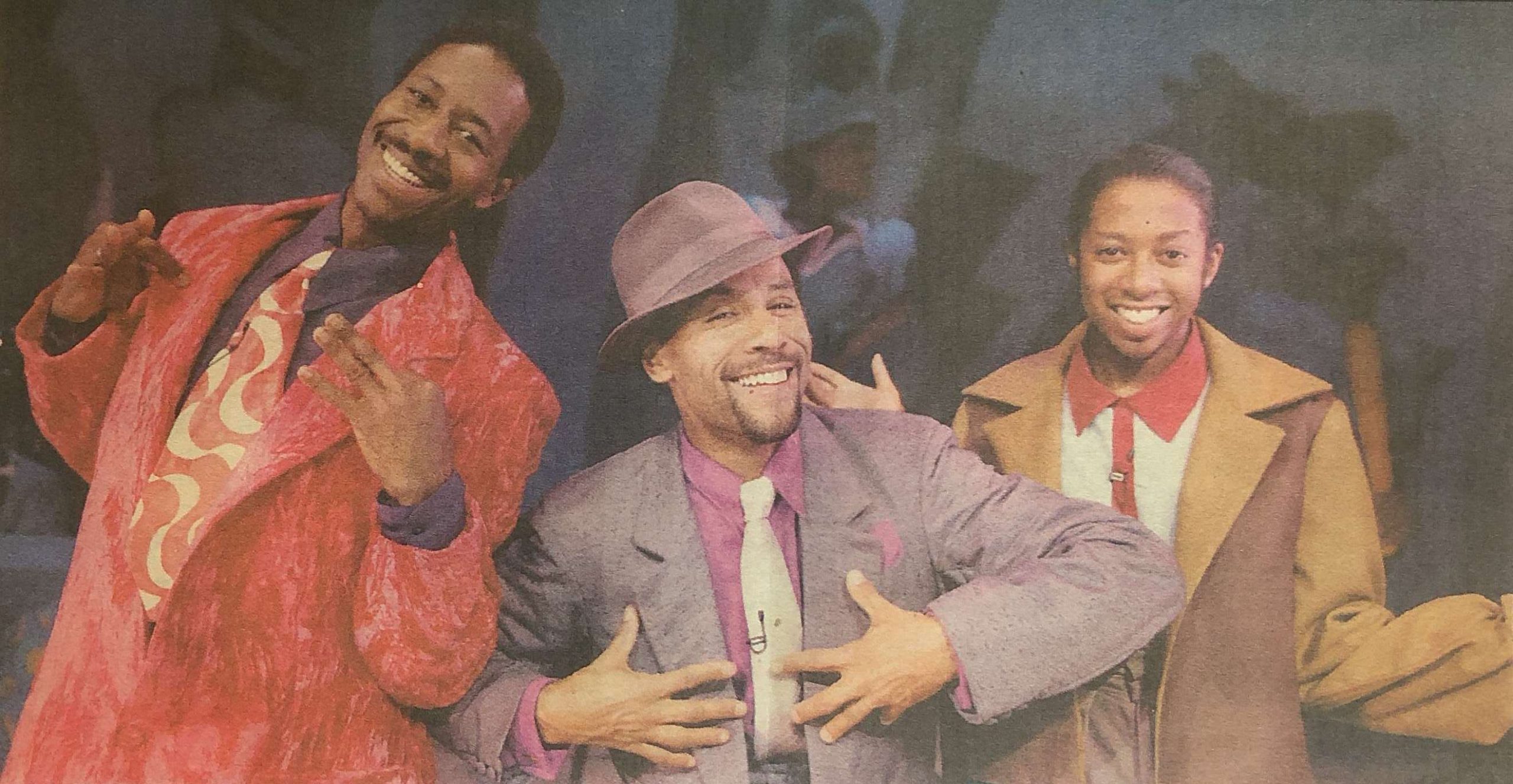

In 1990, another gamble paid off hugely. A celebrated actor and musical performer, Clarke Peters, persuaded the National Theatre to allow him to stage a late-night try-out of the first act of a musical called ‘Five Guys Named Moe’ he was writing. Many producers and theatre directors turned up to see it. Hedley won the rights with the definite offer of a production date, saying he’d be happy if the second act was written during rehearsals. Commercial theatres and orthodox subsidised theatres would never make such an offer.

The reviews were sensationally good, and Cameron Mackintosh bought the production to transfer to the West End immediately. Cameron’s offered deal was more favourable to Stratford East than any transfer deal had ever been, because, as Cameron said “Stratford East took the original risk and therefore deserved it.”

CHAMPIONING A BREAK-THROUGH IN MUSICAL THEATRE

At the start of the last seven years of Hedley’s time at the Royal, the Arts Council and Newham Council had backed a scheme to thoroughly renovate the Theatre Royal and to build an Arts Centre next door to it. This was originally intended to take fifteen months but poor negotiating on the part of Newham Council meant the closure was for very nearly four years, during which time the Royal did small-scale local tours and a short season at the Greenwich Theatre.

However, the Royal’s main artistic drive in the four years of closure became the development of new musicals based on the rap and hip hop music which British young people had been listening and dancing to for twenty odd years. During the twentieth century the waves of new styles of popular music such as ragtime, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll usually took around fifteen years to travel from street popularity into musical theatre. By the end of the twentieth century however, the time lag had become much longer. It was obvious too that Britain with its completely different variety of races to any other Western country had its own range of pop music ready to be capitalised on. Furthermore, if there was a centre for the mixing of the musical styles available to British young people, then it was the East End of London.

Contact was made with potential writers and composers, many of whom had never dreamt of writing a musical before. The plan was to have a four-week workshop, conducted by two members of staff, one black and one Asian, from the Tisch School, a branch of the New York University. There were no other university musical theatre courses in the world. The Theatre Royal’s courses became an annual event with the same two tutors, Fred Carl and Robert Lee, in charge.

There was no age limitation, and there was a particularly strong drive to engage black and Asian participants. There was no fee for the participants and everyone was eligible for £100 per week expenses. The actual course was very practical with an emphasis on short writing projects, with the students finding different partnerships for writing music and lyrics.

The first six months of the theatre building re-opening were deliberately highly typical of the programming expected of the Royal. There was a pantomime followed by a first play by three black women, two of whom happened to be on the board of the Royal. There was an Asian musical with twenty actors written by Niraj Chag and directed by ULTZ. Niraj was a twenty five year old graduate of the first Musical Theatre Workshop. Next in the re-opening programme was one of the theatre’s popular adventure stories, ’20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’ and two uncompromisingly political but entertaining black shows which had been performed elsewhere in their development. Stratford East was keen to give them full support on a large, well-equipped stage.

However, Hedley had miscalculated to a serious degree. This re-opening season fell far short of its box office target. After four year’s closure audiences did not flock back instantly, except for the pantomime. Also he had not realised that a radical change in the way the Arts Council was organised, made during the Theatre Royal’s closure, meant that the Royal was not the direct responsibility of the Arts Council any more, but of a new body called London Arts. The newly appointed director of London Arts proved to be unsympathetic to Hedley’s style of risk-taking. Nor could she appreciate the ground-breaking value of the Royal’s Musical Theatre Project, even at a time when the Arts Council was launching a new campaign to champion diversity in the arts.

In the face of the intransigence of London Arts, Hedley had to cut back programming to a ‘safe’ level and to accept bringing in more shows which had already been staged by other companies. However in his last two years at the Royal he did manage to stage one new musical each year.

The first in 2003 was a rap and hip hop version of a traditional Broadway show by Rodgers and Hart, ‘The Boys from Syracuse’, which was based on the Shakespeare play, ‘The Comedy of Errors’. All the seats were removed from the stalls to enable young people to dance down there, with bouncers in view as in a dance hall. ‘Da Boyz’ was hailed in the press, most significantly by the New York Times. The much-respected American entertainment weekly, Variety, gave it their whole front page, in which it marvelled at how a little theatre in London was given the rights to modernise the show in a way no American theatre had been allowed to do.

In Hedley’s last year at the Theatre Royal he intended the final show he would present would be a break-through musical, called ‘The Big Life’. It used Shakespeare’s ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ as the basis for a show about the Windrush generation coming to England. It had been in development for three years, inspired by the Musical Theatre Project.

Hedley had to resist an attempt to diminish his role before his intended departure date, which was exactly twenty-five years since he went out to rescue the theatre from closure. ‘The Big Life’ was a great success and Hedley became associate producer on its transfer to the West End in the following year. ‘The Big Life’ was the first black West End musical set in Britain and Clint Dyer was the first black director of a West End musical.

A THEATRE OF OPPORTUNITY FOR YOUNG PEOPLE IN NEWHAM: AN EXAMPLE

Clint Dyer went with his Newham school to see Shakespeare’s ‘Pericles’ at his local theatre, the Theatre Royal Stratford East, and he was so astonished the actors from it visited his school, it prompted him to join the Theatre Royal’s Youth Theatre. The Royal became his second home and he would help on events. It encouraged him to be an actor and he rose to appearing in a Mike Leigh production and playing opposite Glenda Jackson in a sketch for one of the Theatre Royal’s many charity nights.

He was an actor in the Royal’s workshops to develop black and Asian directors and was then accepted to do the workshop as a potential director. He became a major contributor to the Theatre Royal’s Musical Theatre Project. He interviewed candidates for it in London and spent several weeks observing the Musical Theatre course at the Tisch school in New York. He became a leading organiser of the first three musical theatre workshops at the Royal. He was accepted as the potential director of Paul Joseph’s ‘The Big Life’ and he worked on it alongside the playwright for three years, which included several rehearsed readings.

He directed it twice at the Theatre Royal and then in the West End in 2005. It was immensely favourably reviewed, but West End success for a first time black director did not lead to other offers. It was over ten years before he received an offer of another production away from Stratford East. However, he is now one of only three people who have worked at the National Theatre as an actor, a writer and a director on full-scale productions. The other two are Harold Pinter and Noël Coward. In January 2021, he was named Deputy Artistic Director of the National Theatre.

PHILIP HEDLEY'S CV

About Philip Hedley

THE EARLY YEARS

In 1961 two members of Littlewood’s company opened the East 15 Acting School based on her rehearsal methods, which in turn were based on the acting theories of Stanislavsky and the movement theories of Laban. Philip Hedley went out to the school in the East End of London as soon as he heard of it. The next day he was a founding student of the school. On graduation two years later, he became an actor/ASM for a year at a repertory theatre, the Liverpool Playhouse, but that experience convinced him he was a director, not an actor. So, he became a teacher at East 15 Acting School to give himself experience directing plays, for three years. He went on to direct plays for LAMDA, for the Royal Court’s young people’s programme and for the Watford Palace Theatre.

His production of Sheridan’s ‘The Rivals’ at the Lincoln Theatre Royal was so successful they offered him in 1968 the post of Artistic Director, which he held for two and a half wonderfully productive years, during which he directed twenty-five plays and produced twenty more. He relished the joys of working with a permanent company of actors on a great range of plays in which the director could deliberately cast parts against type for the actors to extend their range.

The actors worked extraordinarily long hours, performing in the evenings and rehearsing the next play during the day. But they would also perform a music hall on Sunday nights in pubs and other venues around Lincoln. They’d do lunch-time shows occasionally too. They became such a united company they are still meeting up over fifty years later.

This was followed by working in repertory for two years at the Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham, which had an emphasis on young people’s work. Several of the actors were stalwarts of the Lincoln company. Hedley directed new plays by Henry Livings and David Cregan at Lincoln and he did two more of their plays at the Midland Arts Centre.

During 1973 and 1974 Philip was delighted to be asked by Gerry Raffles, the administrator and owner of the Theatre Royal Stratford East, to take on an unusual dual role of being both assistant to him and assistant in rehearsal to Joan Littlewood. It proved to be, as he hoped, two years of extraordinarily valuable experiences, typified by the accompanying photograph of him on the roof of the Theatre Royal dressed as Queen Elizabeth the Second, a role he was thrown into at two hours’ notice.

He directed only one production at the Theatre Royal at this time, which was to have been a revival of Joan Littlewood’s version of ‘A Christmas Carol’, but no-one could find the script of Act One and so that had to be improvised in rehearsal.

Meanwhile requests were piling up for Hedley to return to full-time directing, especially to stage the musicals by an author he had discovered in Lincoln, Ken Lee. This led him to accept guest productions in eight different regional English theatres, plus two productions a-piece in Vancouver and Sydney.

He became particularly known for his ability to free a company of actors up to get them working creatively together. Typical of the reviews he would get with this quality in mind are two he received for his production of ‘The National Health’ by Peter Nichols with Australia’s leading company of actors at The Old Tote in Sydney: “There is over all an assured and relaxed ensemble playing of the kind one was beginning to despair of in the Old Tote Theatre Company, and a feel of common purpose behind the work which gives the whole play a sense of conviction.” (Katherine Brisbane, The Australian). “The actors look like a team at last; the performances are so far ahead of what most of these actors have done this season that one feels like cheering.” (Greg Curran, The Sunday Australian).

Hedley had a particularly stimulating experience in the Sudan staging a play with twenty teachers who were withdrawn from classes for two months to learn about how to direct a play with their own students.

Meanwhile Ken Lee’s musical, ‘Happy as A Sandbag”, attracted West End interest and Hedley staged it at the Ambassadors Theatre. It had good reviews but no stars and it nearly closed after a three-month run. Hedley detected how few of the ticket agents in the West End had seen the show and he involved the cast in a sales campaign which meant the show stayed on for a year and was joined in the West End by another Hedley/Ken Lee production, ‘Leave Him to Heaven’, at the New London Theatre.

THE RESCUE OF THE ROYAL

Over a five-year period three artistic directors had failed to find a formula to make that theatre work after Joan’s departure, and by autumn 1979 the Arts Council was threatening to withdraw its subsidy if Hedley could not, within two years, justify its continuation.

He took up the challenge, and from a standing start, sought out shows to connect with local, East End audiences. There were pantomimes and Variety Nights, sometimes with star names. Events ranged from local school shows, to West Indian poets, to the North East London Police Choir. Joan Littlewood suggested a Victorian melodrama, which transferred to the West End. There was a new musical actually set in the Theatre Royal itself, with music by Ray Davies of The Kinks. There was Hamlet with a celebrated director, Lindsay Anderson, and there was a political farce about Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power, which received the excellent publicity of provoking ‘questions in the House’.

What really raised hopes the Royal would survive was the first play by Nell Dunn, called ‘Steaming’. Set in the East End, it packed the theatre and transferred immediately for a run of over three years in the West End. The Guardian commented “It seems the Theatre Royal Stratford East has finally found a management with both a taste for the popular and welcome audacity.”

Hedley followed this success by confirming his adventurous but local policy with four new plays, three of them set in the East End and all written by young, first-time authors.

It became certain the Theatre Royal would keep its Arts Council grant when, a few days before the decision deadline, the Arts Council’s Director of Drama was quoted in The Times as saying, “Philip has taken a very bold line, and he does seem to have found a dramatic vocabulary appropriate to the area.”

What the Arts Council did not mention was that the ‘bold line’ Hedley had taken included sacking those in charge of the finances and the bar, which involved at one point employing a bodyguard to protect him from threats of bodily harm. In Hedley’s twenty five years, from 1979 to 2004, as director of the Theatre Royal, such high drama off-stage occasionally rivalled the drama on-stage.

GOING LOCAL

The Variety Nights became a regular monthly event, concocted and hosted by a popular local actor, Kate Williams. The Evening Standard newspaper caught the spirit of these Sunday night events thus: “Geriatric gags and brand new sketches, bizarre contortionists and dressy drag queens, loud, brash and often extremely rude.” Famous actors from long-running TV series would pop in for the joy of playing in a comedy sketch to a very lively audience.

The originality of these Variety Nights, their impromptu style mixed with displays of top class expertise, somehow became the heart of the building. Playwrights the theatre wished to commission were encouraged to attend them and to take advantage if they wished of the easy, relaxed style of the give-and-take between the stage and the audience the Royal was acknowledged to have. This style was seen too in Ken Hill’s adaptations of popular novels like ‘The Invisible Man’ and ‘The Phantom of the Opera’, both of which transferred to the West End.

Another populist strand was the creation of shows around the private lives of famous entertainers, such as Old Mother Riley from Music Hall, Josephine Baker from French revue, Fatty Arbuckle from silent film and Sammy Davis Junior from American showbiz. The one show of this genre to transfer to the West End was imported from Australia with one artist, Robyn Archer, playing no less than ten famous women singers.

The audiences became, as in Joan’s later days, an attraction in themselves for coming to Stratford East. As Michael Billington wrote in The Guardian, “Stratford East audiences are generally marvellous. Indeed, if I was compiling a good audience guide they would go to the top of my list.”

Nearly all the plays at Stratford East in Hedley’s time were premieres and many of them dealt with social issues, sometimes comically, sometimes highly seriously, but always from a local point of view. The topics dealt with included the unfulfilling work given to young people on employment schemes, old people being treated in an infantile way in care homes, libraries closing, the damage being done to the National Health Service by the Tories and the narrowing of the curriculum in schools, particularly in relation to the arts. In a play objecting to a new unpopular tax, the poll tax, when some characters were preparing on-stage to go on a protest march, the audience cheered when they realised they could hear real-life people protesting on the same issue outside the nearby town hall.

PIONEERING BLACK AND ASIAN WORK

In the 1990 Prudential Awards for the Arts, the Drama award was won by the Theatre Royal with the following judgement, “Under the present leadership of Philip Hedley, in a time of restriction and entrenchment in the arts the Theatre Royal Stratford East have increased their programme, developed an enthusiastic multi-racial audience of every class and age group, and most successfully promoted new writing with particular emphasis on populist, Afro-Asian, and young people’s work. This is an extraordinary achievement for a theatre of such substantial size but with restricted resources.”

In the nineties Stratford East gained a reputation for trusting black and Asian artists who approached it with ideas for a show. Examples abound. Eight young, black male actors, calling themselves The Posse, asked if they could stage a show at the Royal to illustrate what life was like for black men living in London. They wanted to write it, direct it, act in it and market it. Hedley agreed and the show was a great success at the Royal and on a national tour, and it was a learning experience for the staff of the Theatre Royal.

This was followed up by seven black actresses, calling themselves The BiBi Crew, taking the same journey. The Royal then encouraged a group of African actors and then a group of Asian actors to create their own shows. Finally, four black comedians, male and female, also created their own shows, sometimes solo, sometimes with other actors.

In yet another first in the nineties the Royal backed a new South Asian company, led by Keith Khan, to create the first British version of a Bollywood musical, with two Bollywood stars leading the cast. The show, ‘Moti Roti Puttli Chunni’ and its audience got rave reviews. The Guardian said: “Played in two languages the show offers a brilliant, pop-theatre marriage of East and West.” The Financial Times praised the theatre: “Nowhere else in the London theatre is there such a sense of direct participation”, and added “The audience on the first night was a huge ethnic mix; they all loved it. Part of the pleasure is simply being there.”

EPICS AND RISK

For example, he imported from Chicago a show called ‘Project! A musical documentary’. It had a very large cast, mainly of young black actors, enacting scenes of violence among tenants in tower blocks in a notorious estate, or ‘project’, which the performers actually lived in. Hedley saw it as an apt forewarning of times to come in the UK. The topicality of the show helped sell it and the risk paid off, despite the unhelpfulness of the American embassy when they realised the message behind the show.

Another example of large-scale risk-taking was the staging of the British premiere of ‘The Public’, also with a large cast and many expensive-to-create, surreal settings. It was by the late Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca, who never thought it would be staged, because of its homosexual themes. Hedley wanted to do it, partly because he had available the perfect director/designer for it, ULTZ, and partly because he’d discovered it at a time when there were huge public protests going on about a new law called Clause 28 which was opposed to anything being taught in schools which could be thought to be favourable to homosexuality as a life style.

In 1990, another gamble paid off hugely. A celebrated actor and musical performer, Clarke Peters, persuaded the National Theatre to allow him to stage a late-night try-out of the first act of a musical called ‘Five Guys Named Moe’ he was writing. Many producers and theatre directors turned up to see it. Hedley won the rights with the definite offer of a production date, saying he’d be happy if the second act was written during rehearsals. Commercial theatres and orthodox subsidised theatres would never make such an offer.

The reviews were sensationally good, and Cameron Mackintosh bought the production to transfer to the West End immediately. Cameron’s offered deal was more favourable to Stratford East than any transfer deal had ever been, because, as Cameron said “Stratford East took the original risk and therefore deserved it.”

CHAMPIONING A BREAK-THROUGH IN MUSICAL THEATRE

At the start of the last seven years of Hedley’s time at the Royal, the Arts Council and Newham Council had backed a scheme to thoroughly renovate the Theatre Royal and to build an Arts Centre next door to it. This was originally intended to take fifteen months but poor negotiating on the part of Newham Council meant the closure was for very nearly four years, during which time the Royal did small-scale local tours and a short season at the Greenwich Theatre.

However, the Royal’s main artistic drive in the four years of closure became the development of new musicals based on the rap and hip hop music which British young people had been listening and dancing to for twenty odd years. During the twentieth century the waves of new styles of popular music such as ragtime, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll usually took around fifteen years to travel from street popularity into musical theatre. By the end of the twentieth century however, the time lag had become much longer. It was obvious too that Britain with its completely different variety of races to any other Western country had its own range of pop music ready to be capitalised on. Furthermore, if there was a centre for the mixing of the musical styles available to British young people, then it was the East End of London.

Contact was made with potential writers and composers, many of whom had never dreamt of writing a musical before. The plan was to have a four-week workshop, conducted by two members of staff, one black and one Asian, from the Tisch School, a branch of the New York University. There were no other university musical theatre courses in the world. The Theatre Royal’s courses became an annual event with the same two tutors, Fred Carl and Robert Lee, in charge.

There was no age limitation, and there was a particularly strong drive to engage black and Asian participants. There was no fee for the participants and everyone was eligible for £100 per week expenses. The actual course was very practical with an emphasis on short writing projects, with the students finding different partnerships for writing music and lyrics.

The first six months of the theatre building re-opening were deliberately highly typical of the programming expected of the Royal. There was a pantomime followed by a first play by three black women, two of whom happened to be on the board of the Royal. There was an Asian musical with twenty actors written by Niraj Chag and directed by ULTZ. Niraj was a twenty five year old graduate of the first Musical Theatre Workshop. Next in the re-opening programme was one of the theatre’s popular adventure stories, ’20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’ and two uncompromisingly political but entertaining black shows which had been performed elsewhere in their development. Stratford East was keen to give them full support on a large, well-equipped stage.

However, Hedley had miscalculated to a serious degree. This re-opening season fell far short of its box office target. After four year’s closure audiences did not flock back instantly, except for the pantomime. Also he had not realised that a radical change in the way the Arts Council was organised, made during the Theatre Royal’s closure, meant that the Royal was not the direct responsibility of the Arts Council any more, but of a new body called London Arts. The newly appointed director of London Arts proved to be unsympathetic to Hedley’s style of risk-taking. Nor could she appreciate the ground-breaking value of the Royal’s Musical Theatre Project, even at a time when the Arts Council was launching a new campaign to champion diversity in the arts.

In the face of the intransigence of London Arts, Hedley had to cut back programming to a ‘safe’ level and to accept bringing in more shows which had already been staged by other companies. However in his last two years at the Royal he did manage to stage one new musical each year.

The first in 2003 was a rap and hip hop version of a traditional Broadway show by Rodgers and Hart, ‘The Boys from Syracuse’, which was based on the Shakespeare play, ‘The Comedy of Errors’. All the seats were removed from the stalls to enable young people to dance down there, with bouncers in view as in a dance hall. ‘Da Boyz’ was hailed in the press, most significantly by the New York Times. The much-respected American entertainment weekly, Variety, gave it their whole front page, in which it marvelled at how a little theatre in London was given the rights to modernise the show in a way no American theatre had been allowed to do.

In Hedley’s last year at the Theatre Royal he intended the final show he would present would be a break-through musical, called ‘The Big Life’. It used Shakespeare’s ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ as the basis for a show about the Windrush generation coming to England. It had been in development for three years, inspired by the Musical Theatre Project.

Hedley had to resist an attempt to diminish his role before his intended departure date, which was exactly twenty-five years since he went out to rescue the theatre from closure. ‘The Big Life’ was a great success and Hedley became associate producer on its transfer to the West End in the following year. ‘The Big Life’ was the first black West End musical set in Britain and Clint Dyer was the first black director of a West End musical.

A FOOTNOTE: A THEATRE OF OPPORTUNITY FOR YOUNG PEOPLE IN NEWHAM

Clint Dyer went with his Newham school to see Shakespeare’s ‘Pericles’ at his local theatre, the Theatre Royal Stratford East, and he was so astonished the actors from it visited his school, it prompted him to join the Theatre Royal’s Youth Theatre. The Royal became his second home and he would help on events. It encouraged him to be an actor and he rose to appearing in a Mike Leigh production and playing opposite Glenda Jackson in a sketch for one of the Theatre Royal’s many charity nights.

Clint was an actor in the Royal’s workshops to develop black and Asian directors and was then accepted to do the workshop as a potential director. He became a major contributor to the Theatre Royal’s Musical Theatre Project. He interviewed candidates for it in London and spent several weeks observing the Musical Theatre course at the Tisch school in New York. He became a leading organiser of the first three musical theatre workshops at the Royal. He was accepted as the potential director of Paul Joseph’s ‘The Big Life’ and he worked on it alongside the playwright for three years, which included several rehearsed readings.

Clint directed it twice at the Theatre Royal and then in the West End in 2005. It was immensely favourably reviewed, but West End success for a first time black director did not lead to other offers. It was over ten years before he received an offer of another production away from Stratford East. However, he is now one of only three people who have worked at the National Theatre as an actor, a writer and a director on full-scale productions. The other two are Harold Pinter and Noël Coward. In January 2021, he was named Deputy Artistic Director of the National Theatre.

PHILIP HEDLEY'S CV

Philip Hedley

Awards & Honours

University of East London Honorary Doctorate, 2011

Front row L-R: Philip Hedley, Lois Gould and Yvonne Edgell

Back row L-R: Clint Dyer, Fiston Break and Martin Espindola

| 1991 | ABSA (Association of Business Sponsorship) / The Daily Telegraph Award for Achievement in Sponsorship |

| 1997 |

The Theatre Royal was named as a role model case study by the Commission for Racial Equality

|

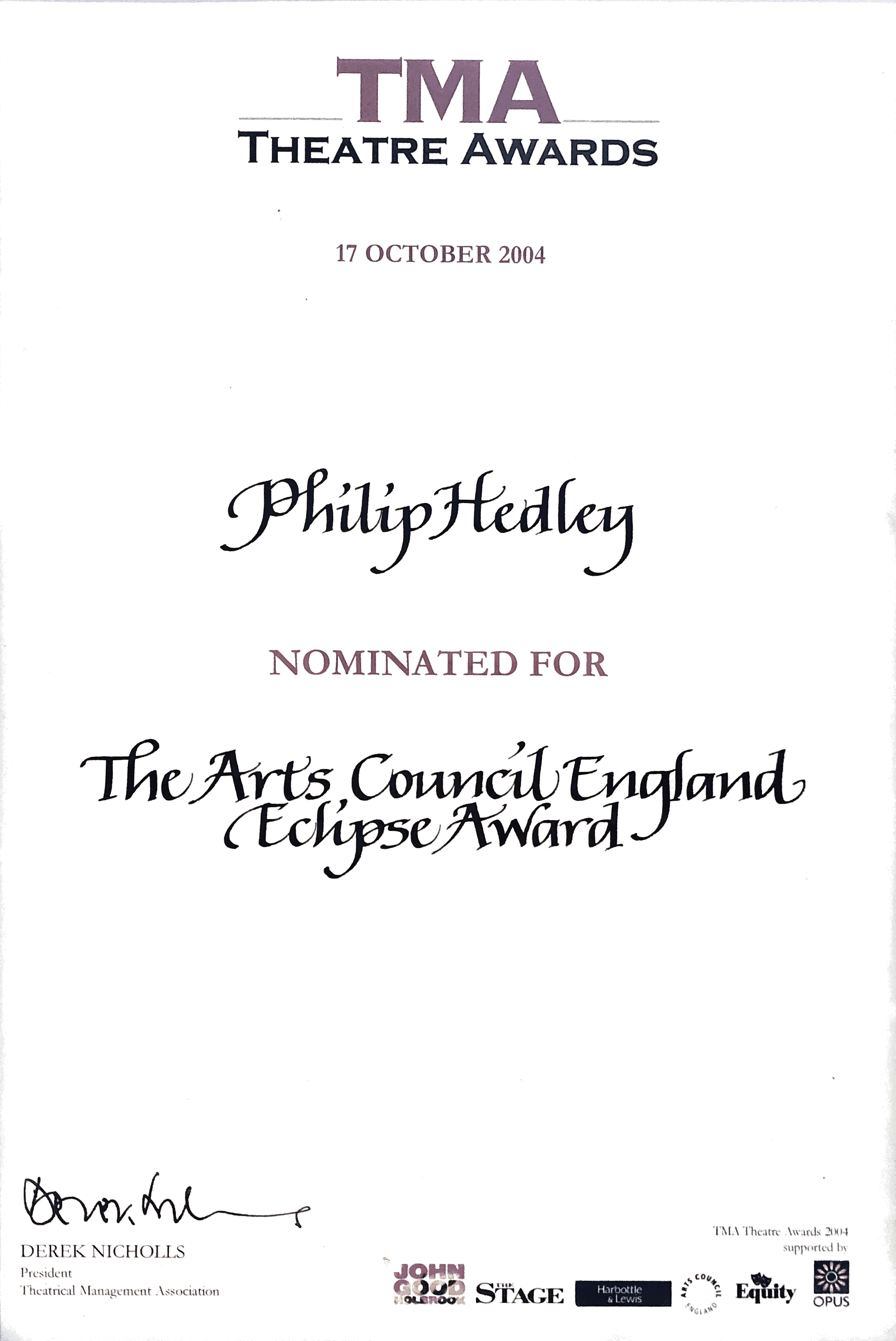

| 2004 | Arts Council England / Theatre Managers’ Association: Eclipse Award for advances against institutional racism in theatre |

| 2005

|

CBE, for services to drama

Egyptian Government Award for Services to International Experimental Theatre and Multiculturalism

Time Out Director’s Award for Outstanding Contribution to Theatre Rose Bruford College: Honorary Fellow Director Emeritus: Theatre Royal Stratford East |

| 2011 | University of East London: Honorary Doctorate |